Introduction

Gender identity consists in the persistent internal sense of belonging to a certain gender (feminine, masculine, or alternative) [1]. Societies build up and reinforce binarism of gender, but one’s perception of his, her or their identity is what truly determines gender [2]. When there is congruence between biological sex and gender identity, the person is cisgender. On the other hand, transgenders or trans people do not identify themselves with their assigned sex at birth [3,4]. People assigned female at birth (AFAB) can identify with a broad gender spectrum [1]. Transmasculine (TM) is an umbrella term to describe people who were AFAB and currently identify within the masculine gender spectrum [5,6]. Also, it is important to emphasize that sexual orientation is totally independent of gender identity [7,8].

In the last decade, the number of transgender people has been increasing, with recent reports suggesting that approximately 2% of the general population consider themselves transgender [9]. Thus, the interest of the scientific community in this understudied population grew. However, most publications focus on hormonal therapy and fertility preservation, with comparatively less attention given to topics such as contraception [2,10-13].

Transgender individuals AFAB are less likely to seek gynecological care in comparison to cisgender women, which renders them at a higher risk for reproductive pathology and unplanned pregnancies [14-16]. Hence, contraceptive counseling in this population is particularly important. The avoidance of health care settings is due in great part to discrimination in the system and limited access to gender – affirming care, but also dysphoria associated with the gynecological visit [16,17]. Bonnington et al. [11] reported that 23% of TM patients postponed medical care due to fear of mistreatment or discrimination. Rodriguez et al. [12] collected data from a national survey in the US from the 6,450 transgender and gender nonconforming study participants, one third reported a negative experience with the medical system. This leads to difficulty in revealing their gender identity to clinicians and only about 40% of the individuals do so [12]. TM report that appropriate and comprehensive health care is still scarce and there is a considerable lack of training and inexperience among providers [2,8,10,14].

In this article, we aim to review and summarize the literature published on contraceptive care and counselling for TM, to highlight the importance of this issue and facilitate clinicians’ practice.

Material and Methods:

To carry out this review, searches were performed in Pubmed and Google Scholar databases using the terms ‘transgender’, ‘transmen’, ‘contraception’, ‘family planning’, ‘reproductive care’. Full available articles from January 2018 to January 2024, written in English or Portuguese, were considered. A manual search of references from identified studies was also conducted and international guidelines were searched for information of interest.

Results

Need for a contraceptive method

When discussing family planning in this population, physicians should ask about the present and future desire for pregnancy, ideally before gender affirming treatments [3,14]. If a pregnancy is not desired at the moment of counselling, practitioners must ask if the person has sexual behaviors that can result in pregnancy [11]. TM who still have uterus and adnexa and engage in sexual activity with a fertile partner who has a penis have contraceptive needs that should be addressed to prevent an unplanned pregnancy [3,5,8,14,18,19]. Nevertheless, contraceptive counselling should be offered to all fertile transgender people, because possible changes in self-reported sexual orientation cannot be excluded.

It is important to take a full gender-inclusive anamnesis, including gynaecological and sexual history. Similar to cisgender women, TM might benefit from a contraceptive method for other reasons, such as achieving menstrual suppression or improvement of pre-menstrual symptoms [3,5,7,8,11,20-22]. Menstruation can be associated to a ‘female body’ which may be very dysphoric, as well as its management (use of pads, tampons, cups) [17,19].

Contraceptive habits

Rates of contraceptive use among transgender individuals are highly variable (20-60%). Barrier methods seem to be the most used ones, followed by contraceptive pills [7]. Cipres et al. [23] reported that among TM who wish to avoid pregnancy, only a few use highly effective methods, and many do not use any method. The most cited reasons for inconsistent use of effective contraception are lack of information, stigma among family planning settings and concern for side effects [11,23,24].

A recently published cross sectional study by Berglin et al. [25] analyzed the use of intrauterine devices (IUD), subdermal implants and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) among TM, for ten years, which increased significantly from 0.3% to 2.3%. A small case series published by Bentsianov et al. [26] on cooper IUD, reported good acceptance by TM individuals.

According to Gomez et al.[24] most TM adolescents do not use contraception or rely only on condom use. Kanj et al. [19] studied 231 TM adolescents: 59% were using hormonal contraception for menstrual suppression, with DMPA being the most used method, followed by combined oral contraception and progestin-only pills. More than half (54%) of sexually active people discontinued their method after achieving amenorrhea with testosterone treatment. As such, it becomes clear that many adolescents are left at risk of unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Advising on contraceptive options and promoting condom use is of paramount importance.

Testosterone and contraception

Exogenous testosterone acts on the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovaries (HPO) axis, rapidly inducing negative feedback [27]. Another consequence is the atrophy of endometrial tissue, which happens in most people, leading to suppression of menses within one to twelve months [5,7,8,20,28,29].

Erroneously, some TM and clinicians have the misconception that testosterone is a reliable form of contraception [3,8,17]. According to Stark et al. [6] the most common doubts among TM individuals are the role of testosterone as a contraceptive method and the possibility of interactions between this drug and hormonal birth control [6]. It is not possible to affirm categorically that pregnancy cannot occur during testosterone treatment [7,30]; it is acknowledged that testosterone’s suppressive effect in the HPO axis may be incomplete and ovulatory cycles may occur [3,5,20,22,27,31]. There are some reported cases of pregnancies in TM people under testosterone treatment, although it is not clear if their compliance was adequate [7,32,33]. It is important to explain TM taking testosterone, that this drug may have teratogenic effects, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy, causing virilization of female fetuses [5,18,20,22,23,28,34]. Information regarding the duration of exposure and its dosage and the risk of teratogenicity is lacking [3]. Testosterone is not a contraindication to any contraceptive method (hormonal or non-hormonal) and there is not, so far, any data on pharmacological interactions [5,7,11,14,17,18,34].

Available contraceptive methods

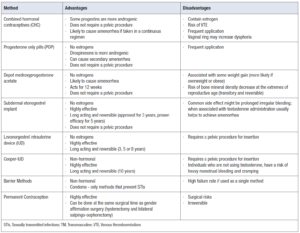

TM people can be offered the full range of contraceptive options, including emergency contraception (EC). There is no restriction to any method on account of the person’s gender identity [3,5,7,11,18,21-23,28,31]. The eligibility criteria are the same as for cisgender women. Nevertheless, TM may have different needs and concerns [7,18,20,35]. Providers should discuss the effectiveness, ease of use, advantages, disadvantages as well as non-contraceptive benefits of the several options [20].

Some contraceptives might have a feminine connotation and be a source of gender dysphoria. Progestogen only pills (POP) or combined hormonal contraceptives (CHC) such as pills, transdermal patch, or vaginal ring, require frequent application - which might remind TM constantly of their gender incongruency [7,21,23,31]. Light et al. [21] reported that half of TM who were taking CHC discontinued the method because they believed it ‘interfered with hormone replacement therapy’ and they ‘did not like extra hormones’ [21]. Although perceived by some as ‘feminine hormones’, there is no evidence demonstrating that the low dose of hormones used in contraceptive methods will significantly alter the masculinization effect of testosterone [5,14,28,34]. Regarding composition, it is known that different progestins have different properties, with more androgenic ones (i.e. levonorgestrel, gestodene and norgestrel) making individuals more likely to have hirsutism and male pattern alopecia, which might represent favorable physical changes to TM people [20].

CHC can be used in a continuous or cycling regimen. It is acknowledged that even in a continuous regimen, different bleeding patterns can occur in cisgender women, and some report unscheduled bleeding (spotting). In TM who are not on testosterone treatment, there is no data published on this topic, but extrapolating from cisgenders, the same is expected to happen [5]. Expert opinion suggests that if amenorrhea has been achieved with testosterone and CHC are taken continuously, it is very unlikely that unscheduled bleeding occurs [11,28]. As CHC have an associated risk of venous thromboembolism and testosterone can increase hematocrit, caution is recommended before initiating the method and other person’s comorbidities and habits should be considered [7,8,11].

POPs are a reasonable option for people who want a less invasive and estrogen free method [28]. They can cause secondary amenorrhea and can be used to limit bleeding and dysmenorrhea. In Europe, there are two types of POPs available for contraception: desogestrel (testosterone - derivative) and drospirenone (spironolactone - derivative). As the first one is more androgenic, it might be more appealing to TM [11].

DMPA is an injectable progestin - only contraceptive given as an intramuscular injection every 12 weeks. It may be appealing for TM due to its potential benefits of complete menstrual suppression in up to 80% of users and the fact that it does not require a pelvic exam [8,29]. It can be associated with some weight gain (more likely in those overweight or obese) and decrease of bone mineral density, which is typically transitory and reversible [7,20,28].

The other available progestin - only methods belong to the group of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs). These methods are considered first line in contraception due to their high effectiveness [29]. Levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUD) and subdermal etonogestrel implants are the most effective ones (>99% efficacy) and in cisgender women are associated with high continuation rates [36].

TM people might feel uncomfortable when pelvic examination is performed to insert an IUD [5,7,20]. However, the method can be appealing since it does not require frequent action to ensure pregnancy prevention - LNG-IUD is approved for three to eight years and Cooper-IUD for ten years [28,37]. Cooper-IUD might be tempting due to the absence of hormones, especially to TM who are amenorrhoeic under the effect of testosterone [35]. However, individuals who have not achieved complete menstrual suppression or that are not using testosterone, have a risk of heavy menstrual bleeding and cramping [5,7,28]. Clinicians inserting IUDs must be aware that TM on testosterone are expected to have subsequent atrophy of the vulva and vagina, thus it is prudent to select smaller speculums and use lubrification [5,15,28,35].

The subdermal etonogestrel implant represents the most effective contraceptive method in cisgender women and it does not require a pelvic procedure for insertion, reasons why it may be a preferred option for TM [28,38]. It is approved for a three-year use; however, it has proven efficacy for at least five years [39]. Nevertheless, it is rarely used for menstrual suppression alone, since a common side effect in cisgender women might be prolonged irregular bleeding [40,29]. When associated with testosterone administration, the implant usually helps to achieve amenorrhea if it has not already occurred [7,28].

Barrier contraception such as internal or external condoms are useful options, especially because they are the only methods that prevent STIs. On the other hand, they have a high failure rate if used as a single method (about 18% with typical use and 2% with perfect use) [18,28,36].

Regarding permanent contraception, TM may look for classical tubal ligation. Some transgender men desire gender affirmation surgery, with hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy [5,7,8,21]. Patients should be informed of the irreversibility of this decision and the risk of regret, as well as the surgical risks.

Emergency contraception (EC)

If there is unprotected vaginal intercourse with risk of pregnancy, EC should be offered in the same posology as for cisgender women: levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, ulipristal acetate 30 mg or copper IUD. Testosterone is not thought to affect the efficacy of any EC option [18,20,29]. (Table1)

Discussion

Contraceptive counselling may be challenging in this population, as TM have unique needs and concerns. Practitioners working in this field should create a gender-inclusive environment, use inclusive language and tailor the counselling. To date, all methods including EC are available for TM as long as eligibility criteria are fulfilled. Concomitant treatment with testosterone is not a contra-indication to any method and no alterations in the masculinization effect of testosterone are expected in people using estrogen containing contraceptives. It is important to explain TM people that testosterone does not provide contraceptive protection, even if amenorrhea was achieved, and that it can have a teratogenic effect. There is little knowledge on safety and satisfaction rates of the different methods in TM, and more prospective studies are needed.

Conclusion

As in cisgenders, there is no perfect method for all. The decision should be shared, and the specific needs and concerns addressed, in order to choose the most appropriate method for that person at that time.