Introduction

Perineal scar endometriosis is the presence of endometrial tissue in the superficial perineum. A history of episiotomy, obstetric tear or perianal intervention often associated with curettage is frequently found [1]. It is a very rare entity occurring after only about 0.01% of vaginal deliveries [2]. Episiotomy scar endometriosis is usually diagnosed late due to the lack of awareness about the condition among general surgeons, resulting in prolonged suffering of the patient and increased morbidity [3].

Case report

A 39-year-old female patient presented with complaints of cyclic pain in the perineal region for one year. The pain appeared during every menstrual period the patient had over the past 14 months. She also complained of dyspareunia. Her menstrual cycles were irregular with normal flow. She had 2 previous vaginal deliveries with a right medio-lateral episiotomy performed both times.

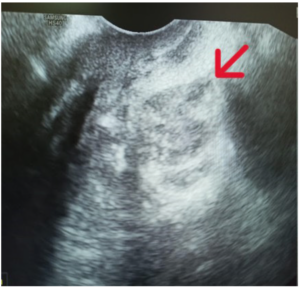

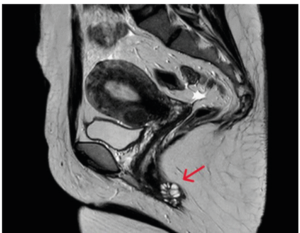

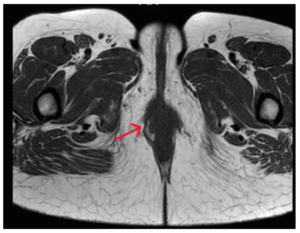

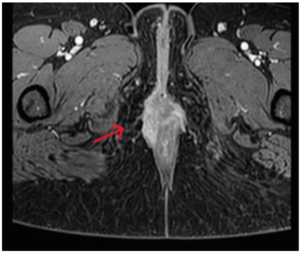

Upon local inspection, a previously healed episiotomy scar was seen. Perineal skin looked normal. Examination revealed a 2×2 cm nodular mass with induration felt at the site of the episiotomy scar. Based on characteristic of the clinical history and examination findings, a probable diagnosis of episiotomy scar endometriosis was considered. Ultrasound of the perineal region showed a non-specific hyperechoic and heterogeneous multi‑loculated complex cystic lesion at the scar site (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of pelvis was done to ruleout extension to the anal sphincter. It showed a multi-loculated lesion in the perineal region, on the right side, corresponding to the scar site measuring 20 x 20 x 10 mm with an irregular wall which intensely enhanced after injection of the gadolinium, while the anal sphincter was intact (Figure 2 - 4).

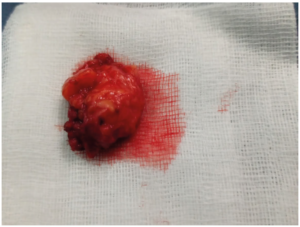

The patient underwent a wide resection of the nodular mass under general anaesthesia (Figures 5 and 6). Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis due to the presence of endometrial glandular epithelium and stroma within the resected nodule. At the 3 month and 6-month post-operative check-ups, the patient no longer had cyclic pain in the perineal region, showed remarkable improvement of the dyspareunia and examination revealed no definite palpable nodule.

Discussion

Extra-pelvic endometriosis is a rare form of endometriosis that affects organs which are anatomically located out of the pelvic region. Multiple clinical forms have been reported in the literature such as abdominal wall and thoracic endometriosis. Scar endometriosis is a frequent type of extra-pelvic endometriosis. It can occur specially in abdominal surgery scar areas following hysterectomy and caesarean section, and in the perineum following vaginal deliveries with episiotomy [2].

Episiotomy is the most commonly performed procedure in obstetric practice. Infection, fistula formation, wound gaping, and painful scarring are its known complications. Development of endometriosis at this site is quite rare and usually reported in the literature as a single case report or small series [3]. Schickele, in 1923, reported on the first case of perineal endometriosis [4].

The pathogenesis of endometriosis include several theories: retrograde menstruation, direct implantation, lymphatic dissemination, coelomic metaplasia, or haematogenous spread. The aetiology of episiotomy scar endometriosis can be explained by the theory of transplantation, mechanical transplantation of endometrial cells to open episiotomy scars during a vaginal delivery [3].

Perineal endometriosis is clinically difficult to diagnose based solely on history and physical examination. Often, diagnosis is only made retrospectively when histopathology of the tissue reveals typical endometrial-like stroma [5]. Zhu et al. [6] have described three typical characteristics of perineal scar endometriosis: 1) Past perineal tear or episiotomy during vaginal delivery; 2) A tender nodule or mass at the perineal lesion; and 3) Progressive and cyclic perineal pain [6].

Our patient experienced perineal pain with a painful node in the episiotomy scar. She previously had two vaginal deliveries with episiotomy in both, which promoted the implantation of endometriosis cells. Imaging of endometriosis is essentially based on two examinations: ultrasound and MRI [1].

Ultrasound is often the initial imaging modality for perineal scar endometriosis. It shows a non-specific appearance of nodules which are usually hypoechoic and heterogeneous (depending on their solid and / or liquid component), sometimes hyperechoic (hemorrhagic forms), with external limits that are readily blurred and irregular, having a variable shape and size (depending on the amount of blood and fibrosis, the time of the cycle and / or the current medical treatment [1,7].

Advancements in endo-anal ultrasound have aided to the planning of surgery for perianal and anal lesions. Its practical use lies in determining the nature of the lesion, assessing the sphincter involvement, and ruling out other possible differentials, such as a perianal abscess or haemorrhoids [5-8].

MRI is currently the best imaging method to assess endometriosis. It finds its indications as well in endo-pelvic as in extra-pelvic locations [1,8]. MRI, due to its high contrast resolution, can identify the extent of the lesion and its relation to the anal sphincter complex. This aids the surgeon to decide upon the sphincter reconstruction if there is evidence of anal sphincter invasion by the lesion [7].

Treatment of choice is wide excision of the lesion and medical management, if required. Only medical treatment with the use of progestogen, oral contraceptive pills and danazol is not effective and gives only partial relief of symptoms. Recently, there has been reports of the use of gonadotropin agonist but only with prompt improvement of symptoms with no change in the lesion size. These patients need to be followed up because of the chances of recurrence, which require re-excision. In case of continual recurrence, possibility of malignancy should be kept in mind [6,9].

In our department, therapeutic abstention is the rule in asymptomatic forms (30% of endometriosis). Medical treatment is either prescribed alone: is effective on pain and consists of stopping menstruation with progestins (Danazol) or GnRH analogues; either in addition to borderline or incomplete surgical treatment. The treatment of choice includes wide local excision of the endometriotic tissue with a margin of 1 cm of healthy tissue.

Conclusion

Perineal endometriosis is a rare entity. the diagnosis must be evoked when there is cyclic pain at the level of the episiotomy scar. Clinical examination, coupled with the ultrasound or even the MRI, will guide to the diagnosis. Wide excision is the treatment of choice as medical treatment may not produce lasting relief.