Beatriz Ferro, Vanessa Vieira contributed equally to this work.

Introduction

Physical activity is defined as any movement associated with an energy expenditure above resting levels, including daily activities such as sweeping, mopping, walking the dog, among others. In contrast, physical exercise (PE) refers to planned, structured, and repetitive movements performed with the objective of improving or maintaining physical fitness. As such, PE is a key component of a healthy lifestyle [1,2].

The benefits of regular PE in the general population are well established, and growing evidence supports its positive impact during pregnancy [1,3]. Even for women who were previously inactive, initiating PE during pregnancy is recommended, provided there are no contraindications [2,4].[2,4]. However, despite existing evidence, healthcare professionals' guidance on PE during pregnancy remains inconsistent [1,5]. This inconsistency, combined with the fatigue often experienced during pregnancy and concerns regarding potential risks to the fetus, can further reduce adherence to beginning or maintaining PE. A lack of encouragement from healthcare providers may also contribute to this low adherence [2,5].

Pregnancy induces physiological changes across multiple organic systems to support fetal development and growth. These adaptations must be considered by healthcare professionals when prescribing PE [1,4,6]. In the cardiovascular system, pregnancy leads to increased blood volume, heart rate, and cardiac output, along with reduced peripheral vascular resistance, leading to lower blood pressure in healthy pregnant women [1,4,7]. In the respiratory system, minute ventilation increases by nearly 50%, primarily due to increased tidal volume, resulting in higher oxygen consumption and a reduced oxygen reserve [1,4,7]. Given the complexity of these physiological changes, PE during pregnancy should be tailored to each woman’s characteristics and gestational stage. Ideally it should be prescribed and monitored under multidisciplinary supervision [1,5].

Several observational studies suggest that PE during pregnancy may be associated with benefits such as reduced risk of gestational diabetes, better weight management, lower likelihood of assisted delivery or cesarean section, quicker postpartum recovery, and reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression [2,4]. However, further research, particularly randomized controlled trials, is needed to confirm these associations.

Since PE reduces maternal body fat percentage, placental oxygen transfer increases, and carbon dioxide diffusion decreases, thus, contributing positively to fetal development and lowering the child's future cardiovascular risk [5]. Some preliminary evidence suggests a possible link between maternal exercise and enhanced fetal brain development, with a few studies indicating higher IQ scores in children of mothers who exercised during pregnancy. However, these findings remain inconclusive and require further investigation to establish causality {5].

According to current guidelines, such as those from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), PE is recommended during pregnancy for about 20 to 30 minutes per day, on most days of the week, provided there are no contraindications [1-5]. The choice of exercise should favor static, aerobic, or resistance activities while avoiding high-impact activities that alter the center of gravity, with appropriate adaptations made throughout pregnancy [1,6]. For instance, in the second half of pregnancy, the supine position may compromise venous return due to aorto-caval compression by the gravid uterus, potentially leading to maternal hypotension [1].

Contraindications to PE can be absolute, such as membrane rupture, threatened preterm labor, persistent vaginal bleeding, and cervical insufficiency, or relative, including recurrent pregnancy loss, history of preterm birth, poorly controlled chronic hypertension, musculoskeletal disorders, and eating disorders [1,3]. However, even in cases of relative contraindications, women may still be encouraged to modify their physical activity to safely benefit from its positive effects.

The primary objective of this study was to assess PE habits of pregnant women attending at a tertiary hospital. Secondary objectives included analyzing their sociodemographic characteristics, the type and frequency of the performed exercise, and whether PE is prescribed or recommended by healthcare professionals.

Methods

A descriptive observational study was conducted through the analysis of a questionnaire completed by pregnant women between August 2022 and May 2023 at a Portuguese tertiary hospital. The sample comprised representative members of the target population, selected through a non-probabilistic, accidental, and convenience sampling method. It was considered non-probabilistic because not all individuals in the population had an equal chance of being selected. The sampling was accidental as it included participants who were accessible and present at specific locations during the study period.

Additionally, it qualified as a convenience sample because it was drawn from a segment of the population that was readily available. Study participants were selected from various clinical settings of the hospital, including outpatient consultations, ultrasound appointments, and the emergency department. Exclusion criteria were inability or unwillingness to provide informed consent, incomplete or improperly filled questionnaires that compromised data integrity, cognitive or language barriers that prevented adequate understanding or completion of the questionnaire and any known medical or obstetric conditions that contraindicated physical activity, as these could significantly bias responses related to exercise habits.

The selected participants were asked to complete a confidential questionnaire consisting of 30 questions, with an estimated completion time of approximately five minutes. The questionnaire collected personal and sociodemographic data (maternal age, employment status, educational level), anthropometric data (height and weight), clinical and obstetric history, sports and PE habits (before and during pregnancy), and whether they had received guidance from a healthcare professional regarding PE.

Upon receiving the questionnaire, participants were informed of the study’s objectives, assured of data confidentiality, and given the option to decline participation without any consequences. The study was conducted in accordance to the guidelines set by the hospital Clinical Research and Ethics Committee and adhered to the principles outlined in the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® version 27. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables are presented as absolute frequencies (n) and percentages (%), while continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation when following a normal distribution and as median with minimum and maximum values when they did not follow a normal distribution. Chi-square test was used for comparing categorical variables. A p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

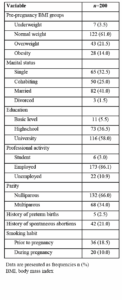

A total of 200 pregnant women were included in this study, comprising the sample (n=200). The median age was 32 years, ranging from 18 to 45 years, with 35.5% (n=71) being 35 years or older. The median pre-gestational body mass index (BMI) was 23.5 kg/m² [16.5–42.2], with 35.5% (n=71) classified as overweight or obese.

Regarding smoking habit, 18.5% (n=37) reported smoking before pregnancy, of whom 47.2% (n=17) stated they had quit smoking during pregnancy. Most participants were married or cohabiting (66%, n=132), had completed a higher education level (58%, n=116), and were employed (86.1%, n=173).

Concerning obstetric history, most participants were nulliparous (66%, n=132), while among the multiparous women, 77.9% (n=53) had a history of vaginal deliveries. Additionally, 2.5% (n=5) had a history of preterm birth, and 21.0% (n=42) had experienced spontaneous abortion. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics and obstetric history of the participants.

When asked about their current pregnancy, most participants reported that it was planned (75.5%, n=151), 24.0% (n=48) stated that it was unplanned but desired, and one case (0.5%, n=1) reported an undesired pregnancy. Additionally, 32.0% (n=64) considered their pregnancy to be of high-risk.

Regarding the distribution of participants by trimester, 23.0% (n=46) were in the first trimester, 22.0% (n=44) in the second trimester, and 55.0% (n=110) in the third trimester.

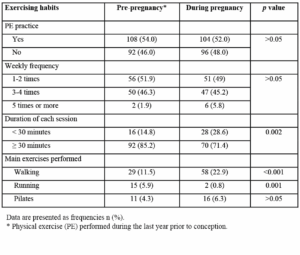

In terms of PE performed in the year prior to pregnancy, 54.0% (n=108) reported engaging in PE, with most exercising performed one to two times per week (51.9%, n=56), and 85.2% (n=92) performing PE sessions lasting 30 minutes or longer. The most common types of exercise included gym workouts (50.0%, n=54), walking (26.9%, n=29), running (13.9%, n=15), and Pilates (10.2%, n=11). The characterization and comparison of exercising habits before and during pregnancy are presented in Table 2.

When questioned about the potential benefits and risks of carrying out PE during pregnancy, 99.0% (n=198) believed that it contributes to a healthier pregnancy, facilitates labor, and improves maternal health, while 92.5% (n=185) believed it enhances fetal health. Conversely, 17.0% (n=34) associated PE with urinary incontinence, 2.6% (n=5) considered it a risk to maternal health, and 1.5% (n=3) perceived it as a risk for fetal health. Additionally, 10.0% (n=20) believed that PE during pregnancy had no impact.

Regarding PE practice during pregnancy, 52.0% (n=104) reported engaging in PE at some point during their pregnancy, with most exercising one to two times per week (49.0%, n=49) and for at least 30 minutes per session (71.4%, n=70). The most common types of exercise included walking (55.8%, n=58), gym workouts (22.1%, n=23), Pilates (15.4%, n=16), and water aerobics (14.4%, n=15).

Comparing pre-pregnancy and pregnancy exercising habits, a lower percentage of pregnant women engaged in PE sessions lasting 30 minutes or longer (p=0.002). Regarding exercise type, there was a higher percentage of women that chose walking during pregnancy (11.5% vs. 22.9%, p<0.001), whereas fewer women opted for running (5.9% vs. 0.8%, p=0.001) and gym workouts (21.3% vs. 9.1%, p<0.001).

The main reasons for not engaging in PE during pregnancy were lack of time (41.7%, n=40), fear of harming the baby (13.5%, n=13), medical advice (12.5%, n=12), dislike of exercise (30.2%, n=29), urinary incontinence (5.2%, n=5), abdominal or lower back pain (36.5%, n=35), and the absence of nearby gyms (13.5%, n=13).

Overall, 49.5% (n=99) reported modifying their exercise habits during pregnancy, mostly in the first trimester (66.7%, n=66), followed by the second (22.2%, n=22) and third trimesters (11.1%, n=11). The most common changes included: reducing weekly frequency (75.9%, n=63), lowering exercise intensity (86.7%, n=72), shortening session duration (76.5%, n=62), and altering the type of performed exercise (66.7%, n=50). The primary reasons for these changes were discomfort or pain (12.6%, n=32), medical advice (10.3%, n=26), and concerns about pregnancy-related risks (9.1%, n=23).

Among those who did not engage in PE in the year before pregnancy, 26.1% (n=24) initiated PE during pregnancy. Conversely, among those who were already active before pregnancy, 30% (n=48) maintained their exercise habits throughout pregnancy.

Regarding guidance from healthcare professionals, 11.9% (n=30) were advised to follow absolute rest, while 71.1% (n=135) reported being encouraged to engage in PE during pregnancy. A comparative analysis between pre-pregnancy and pregnancy exercising habits and the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample revealed that a higher percentage of women who engaged in PE before pregnancy had completed higher education (64.9%) (p=0.032). Additionally, there was a higher percentage of unemployed women in the group that did not engage in PE before pregnancy (18.2% vs. 6.8%, p=0.017). There were no other statistically significant differences observed between other sociodemographic characteristics and exercising habits during pregnancy.

Discussion

This study reveals a key finding: although the vast majority of pregnant women (99.0%) believe that PE contributes to a healthier pregnancy, there was a marked reduction in PE frequency, intensity, and duration during pregnancy.

Many participants shifted from higher-intensity activities such as running and gym workouts to lower-impact options such as walking. Furthermore, only a small proportion of women met the recommended levels of PE during pregnancy. Despite increased awareness and recognition of the benefits of PE, barriers such as lack of time, physical discomfort, fear of harming the baby, and conflicting medical advice significantly contributed to the decline in PE during pregnancy. These results underscore the disconnection between knowledge and behavior, highlighting the need for practical strategies to support pregnant women in maintaining adequate PE.

Lack of time and pain were among the most frequently reported barriers to PE during pregnancy. These challenges can be better understood through behavioral frameworks such as the Health Belief Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior. These models suggest that perceived barriers—like discomfort or limited time—can reduce motivation to engage in PE, even when individuals recognize its benefits. Addressing these issues requires not only clinical support for managing physical symptoms but also strategies to enhance self-efficacy, reshape perceptions of risk, and promote time-efficient, adaptable exercise options tailored to the realities of pregnancy [8].

Healthcare providers play a crucial role in addressing these barriers. Integrating evidence-based, individualized counseling into routine prenatal care may encourage women to start or continue performing PE during pregnancy throughout pregnancy. This includes offering clear trimester-specific exercise plans, reassuring women about the safety of PE, encouraging participation in low-impact group activities such as prenatal yoga or walking groups, and addressing discomfort through physical therapy or exercise adjustments. At a broader level, healthcare systems should provide educational materials that dispel common myths, develop community-based programs with flexible schedules, and ensure access to prenatal fitness options, especially for women with limited time or resources [5].

According to leading guidelines [1,10], such as those from the ACOG and the World Health Organization (WHO), pregnant women with uncomplicated pregnancies should aim for PE on most days of the week, ideally five to seven times. The total duration should reach at least 150 minutes per week, distributed across 30-minute sessions. The recommended intensity is moderate, allowing for conversation during the activity, with preferred types being aerobic exercises like walking, swimming, stationary cycling, or light resistance training. In our sample, the majority did not meet this threshold, and many modified their routines early in pregnancy, this suggests a need for more effective education and reassurance, particularly in the first trimester when changes in behavior are most likely to occur.

Pregnant women should maintain adequate hydration, wear supportive and comfortable clothing and footwear, avoid overheating, and refraining from high-risk activities such as contact sports or those with a risk of falling.

Additional findings of the study include the influence of sociodemographic factors on the rate of performing PE before pregnancy. Women with higher education levels and those who were employed were more likely to engage in PE before pregnancy, findings that align with previous studies [10].[10].

However, these factors appeared to have less influence during pregnancy itself, suggesting that the physiological and emotional changes of pregnancy may override previously established habits.

Interestingly, 26.1% of women who were not performing PE before pregnancy began engaging in PE during pregnancy. This shift may reflect the positive impact of prenatal counseling or heightened health awareness during this period [11]. Nonetheless, this highlights the need for early education and sustained support to ensure that these changes persist.

While 71.1% of participants reported receiving encouragement from healthcare professionals to engage in PE, 11.9% were advised to maintain absolute rest. This is noteworthy because current evidence shows that routine PE during pregnancy should not be commonly recommended, due to lack of evidence supporting its benefit the prevention of preterm birth and known risks such as deconditioning (loss of fitness) and thromboembolism. Persisting on this outdated recommendation highlights the gap between guidelines and clinical practice and underscores the importance of continuing education for providers [1,12].

Advanced maternal age (≥ 35 years) was present in 35.5% of participants, reflecting the current trend of pregnancies occurring at increasingly older ages. These findings align with previous similar studies, with extremes ranging from 16 to 45 years [10,13,14]. Furthermore, no significant differences in PE practice were identified when comparing older pregnant women (≥ 35 years) with younger pregnant women (<35 years) (p>0.05).

Sociodemographic data of our study indicate that most participants were married or cohabiting, had completed a higher education level, and were employed, which is consistent with similar studies and appear to follow the trend of decreasing unemployment rates at the national level, according to the National Institute of Statistics from Portugal [13].[13]. These factors indicate a population profile with favorable socioeconomic conditions, which can positively impact the pursuit of prenatal care and adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Regarding smoking habit during pregnancy, our study presents a higher percentage of pregnant women who ceased smoking during pregnancy (47.2% vs. 35%) comparing to other previous studies [15,16]. This difference may be attributed to increased awareness campaigns regarding the effects of smoking during pregnancy and counseling from healthcare professionals in Portugal.

One limitation of the present study is related to the limited availability of similar research reported in the literature, making it challenging to compare results. Additionally, the study utilized a non-probabilistic sample, which may restrict the generalizability of findings, as the population was limited to a specific region of the country and received prenatal care in a hospital setting. Further studies with larger samples are required to allow a better comparison and generalization of results.

Conclusions

This study highlights that although most pregnant women recognize the benefits of PE during pregnancy, participation does not follow current recommendations, with a notable shift toward lower-intensity activities such as walking. While some women initiate or maintain PE during pregnancy, many reduce frequency, intensity, and duration due to discomfort, medical advice, or the fear of risks. Sociodemographic factors like higher education and employment status were associated with greater PE engagement before pregnancy, though these had less influence during pregnancy itself. Our findings underscore the importance of personalized professional guidance to support safe and sustained PE throughout pregnancy and to address common barriers. Further research with larger, more diverse samples is needed to validate and expand our results.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines set by the hospital Clinical Research and Ethics Committee and adhered to the principles outlined in the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed of study’s objectives, assured of data confidentiality, and given the option to decline participation without any consequences.

Author’s contribution

Beatriz Ferro and Vanessa Vieira designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, wrote, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Daniela Albuquerque collected the data and approved the final manuscript.

Filipa Marques and Joana Palmira Almeida had substantial contributions to conception and design, relevant critical review of intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published.

Isabel Santos-Silva made substantial contributions to conception and design, interpretation of data, relevant critical review of intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study can be made available from Beatriz Ferro upon reasonable request.